The interwebs are all abuzz with news from Comic-Con, where it seems everybody gets to have fun dressing up as their favorite character. I play dress-up every day here at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, but my costume isn’t much fun.

Let’s work from the feet on up:

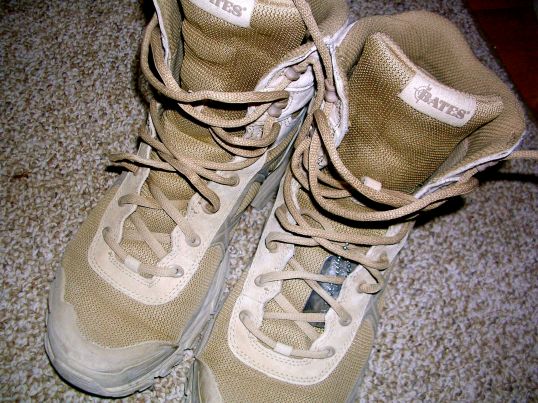

These are my summer-weight boots. If you’ve followed me from the beginning, you know how fussy I am about my boots! Although this footwear is feather-light with lots of breathable fabric, it still feels like I’m wearing ovens on my feet.

That thing tucked into the laces on my left boot? One of my dog tags (I wear the other around my neck). I’ve had several people ask me why I put the tag in my left boot. Picking a tag foot was something I actually spent some time pondering. I have a small red birthmark on the third toe of my right foot (which you can see in this blog post), so if my right foot/leg gets blown off the chances are good it can be identified as mine by the birthmark. That’s why the tag is in the left boot — I want that dismembered limb reunited with the rest of me. These are the things you have to think about in a war zone that would never cross your mind anyplace else.

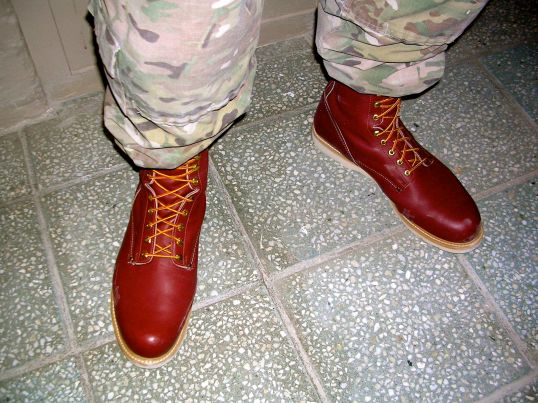

Boots are a big deal here, and having ill-fitting boots can make you miserable. My coworker Darryl is 6’5″ and a mountain of a man, and he’s on his feet all day doing construction management and inspections. He wears out boots quickly and he’s had a devil of a time finding big enough boots that fit right. Finally, after months of limping around in uniform boots that fit all wrong, he got himself an exception to policy so he could wear boots that fit, even though they don’t match his uniform:

Those big red boats are lumberjack boots, and Darryl is in heaven! He jokes that somewhere out there Ronald McDonald is going barefoot…

My trousers have cargo pockets all over the place, and I’ve learned how to pack those pockets in the most optimal way for myself. The pocket on my right calf contains my tourniquet:

Almost everybody carries one, and many people carry two (one in a leg pocket, one in a sleeve pocket). Most people also write their blood type on the red tab, but I don’t. My hope is that if I ever have to use it, it will be on somebody else and I don’t want my blood type confusing the medical staff. With all the Indirect Fire (IDF) attacks here, there is a lot of shrapnel flying around and several people have been seriously injured, so I always carry my tourniquet.

The pocket on my right thigh is where I keep my camera, sunglasses, cell phone, pedometer and fan. I have several fans and I’m not shy about fanning my sweaty, broiling self when the air conditioning is not adequate to keep me comfortable. Seriously, check out this forecast:

Totally uncalled-for.

I don’t put anything in my left-side cargo pockets except my hat. I’ve learned that sometimes you are in a crowded place and the IDF alarm goes off (INCOMING-INCOMING-INCOMING), and when you hit the floor there might not be enough room to lay flat on your belly among all the other people, so you have to lay on your side. I leave my left side pockets clear so I can lay on my left side comfortably (without hard, pointy things poking into me) in crowded places under attack. Again, things you don’t think about except when you’re in a war zone.

On my upper body I wear a plain Desert Sand colored t-shirt, on top of which I wear this rather heavy blouse:

The patch with my last name and the patch identifying me as a Department of Defense civilian are stitched in brown, which means I work for the Air Force (even though I’m assigned to the Army Garrison here). If the stitching on those patches were black, that would mean I’m an Army employee.

The triangle that says “US” is a placeholder — if I were military, that spot would show my rank. When I first got here, I noticed a lot of people approaching me on the walkways were staring at my chest all the time and it was creepy and uncomfortable. Then I realized they were trying to figure out my rank. Military members walking around outside have to salute higher-ranking personnel, and it’s sometimes difficult to tell the rank until you’re very close. It didn’t help that my lanyard often hung in the way and obscured my “rank”. Now I try to make it as obvious as possible from as far away as possible that I don’t need to be saluted.

Like the trousers, the blouse is very layer-y with lots of pockets and double-fabric reinforced areas. These garments are not very breathable, so I’m roasting most of the time wearing this uniform in the heat of summer.

The patches you wear on your sleeves identify your nationality, unit(s), and mission. On my right arm, the flag shows that I’m an American (click here to find out why it’s “backwards”) and the round patch identifies me as falling under the 966th Air Expeditionary Squadron (the Air Force unit charged with keeping tabs on all us Air Force personnel regardless of the unit to which we’re assigned):

On my left sleeve, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) patch says I’m here for their mission, and the patch with the mountains, guns, and sword tells people I work for the US Army Garrison:

I wear a lanyard around my neck with a pouch that carries my ID card, emergency phone list, and debit card:

Like I mentioned above, I tuck the pouch into my blouse pocket so the troops approaching me on the sidewalk can tell I’m not someone to salute. To top everything off, I get my choice of patrol cap or boonie hat (neither of which does my hairdo any favors):

I wear the boonie hat in the summer not only because of the sun protection but because summer is the season for the “100 Days of Wind”. It’s very dusty and gusty, and the boonie hat has a strap so I have some hope of keeping it on my head when the winds start howling.

So, that’s how I get into costume for my job here in Afghanistan. I call it “my costume” not to mock the military members who serve in uniform, but because I’m a civilian and I really do feel like I’m playing dress-up. Wearing the uniform causes people to show me respect I feel I haven’t earned because I haven’t made the commitment the military members have made, nor am I expected to make the sacrifices that may be required of them.

On the other hand, the IDFs don’t discriminate when they come flying in. I have to hit the deck and make my way to the bunkers with everybody else, military and civilian alike. We’ve had a lot of IDF action over the last couple of days due to Eid al-Fitr: apparently one way insurgents like to celebrate the end of Ramadan is to shoot rockets at Bagram Airfield. I can think of better party games than that, just like I can think of more comfortable clothes to wear to work — but nobody is asking for my opinion.

Eid Mubarak!

MM